I’m not a great cook, but I nevertheless love to read books that include a fair amount of food-writing. By that, I don’t mean cook books – I can’t “taste” food by reading a recipe the way some of my “foodie” friends can. And I also don’t mean books like Gwyneth Paltrow’s, which are essentially recipe books with some background about why the author is interested in food, family and healthy life-choices….

The food books I love are novels, memoirs, travel books, etc., in which food helps drive the plot; or in which food is the vehicle which illuminates the characters, or is shown to “form” their personalities, or describes their relationships with others; or which illustrate how food and cooking can serve to comfort or empower.

This is a large and varied genre.

WOMEN WHO EAT is a collection of essays by women in which they describe their various relationships with food. Some are professional cooks, but most are writers who tell of their feelings and memories of food. It’s a celebration of food and of women who enjoy food without shame or apology.

There are lovely essays about bonding with grandparents while working in the kitchen together; there are reflections about the pleasure of making a meal, because it is one of the few activities in which there are no “loose ends,” as a meal “has a beginning, middle, and end.” Simple and clear.

WOMEN WHO EAT is a collection of essays by women in which they describe their various relationships with food. Some are professional cooks, but most are writers who tell of their feelings and memories of food. It’s a celebration of food and of women who enjoy food without shame or apology.

There are lovely essays about bonding with grandparents while working in the kitchen together; there are reflections about the pleasure of making a meal, because it is one of the few activities in which there are no “loose ends,” as a meal “has a beginning, middle, and end.” Simple and clear.

Because I'd had similar experiences, I especially enjoyed the essay by Pooja Makhijan, whose mother would put exotic “aloo tikis” into her lunch box, so unlike the “American” food her classmates had in theirs – and theirs were the kind of lunches she'd always longed for!

With the same good intentions, my mother would often pack my brown paper bag with a [healthy] whole tomato to bite into like an apple (juice running down my chin and neck) and a sandwich on rich rye bread. And oh, how I, too, longed for a sandwich on real “American” white bread!

Most of the essays in this book were entertaining, though none felt entirely "new." And I hope you'll excuse me if I say that they're a bit like appetizers before the main course....

Most of the essays in this book were entertaining, though none felt entirely "new." And I hope you'll excuse me if I say that they're a bit like appetizers before the main course....

In Ruth Reichl’s memoir, TENDER AT THE BONE, the former restaurant critic and editor of the now defunct GOURMET magazine remembers a childhood that prepared her for a future in the food world. Reichl describes in sometimes hilarious detail, her early and strange connection with food.

Her "manic-depressive" mother loved to entertain, and depending on her mood, or on the latest “bargain” of ready-for-the-garbage food, or whatever decaying carcass she found in her larder, she often served food that was spoiled or moldy. Before the age of 10, Reichl understood that “food could be dangerous” and saw it as her “mission…to keep Mom from killing anybody who came to dinner.” She sometimes stood in front of guests to prevent them from getting to the buffet; and bluntly told her own friends, “Don’t eat that,” as they unsuspectingly plunged their spoons into dishes like bananas in green sour cream.

Her role as “guardian to the guests” made her aware of food in a way that might not have occurred otherwise. She began “sorting people by their tastes” and finding that she could learn a lot about people from the foods they chose and the places in which they liked to eat. And she continued to observe and learn about food as she made her way from New York to a French boarding school in Montreal and a commune in Berkeley; as she came under the wings of people like Alice Waters and James Beard.

Liberally sprinkled with recipes, this adventure in food has a happy ending, as Reichl got to live her passion of cooking and eating and teaching people about food.

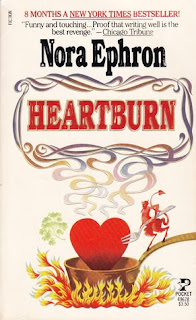

Nora Ephron’s HEARTBURN is a slyly fictionalized account of her divorce from journalist Carl Bernstein. The novel’s heroine, Rachel, is a food writer, and Ephron uses food and recipes as the conceit with which to describe Rachel’s relationship and marriage, from its beginning to its end.

Seven months pregnant at the time that she discovers that her husband is having an affair, Rachel reviews the trajectory of their marriage:

When first in love, [she] prepares labor-intensive and time-consuming “crisp potatoes;” when they settle into a married life busy with a child and home improvements, it’s the complacency and self-assuredness of “peanut butter and jelly on white bread.” (Yum!) With the knowledge of her husband’s affair, it’s “heartburn” and a punishing refusal to give him her wonderful vinaigrette recipe. Then it’s self-pity and the comfort of mashed potatoes…. Finally, she accepts that she can do without him, and expresses that acceptance by throwing a pie in his face – and by her willingness to give him that vinaigrette recipe after all: in essence, she is saying, “You can have it, and I’m out of here!”

Forget the Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson film of the same name; this is a delicious, insightful, and wickedly funny book. And the great recipes are an added bonus.

More and more common in the food-writing genre are the books that tell of people moving to a “foreign” country and navigating their way through that new landscape. And food is a major player in these journeys.

In Marlena De Blasi’s A THOUSAND DAYS IN VENICE, American restauranteur and cookbook writer De Blasi tells of her love-at-first-sight romance with a Venetian man she sees across a crowded room – really! – and of her move to Venice to be with him. And for all its beauty, it’s an inhospitable Venice she comes to, steeped as it is in old traditions which have no room for newcomers.

But De Blasi haunts the local food markets at 5:00 AM each morning, and with her knowledge and love of food, she seduces the locals and becomes “one of them.” Then, she repeats this feat in her sequel, A THOUSAND DAYS IN TUSCANY, where she eats at the small local restaurant to which everyone in the neighborhood – including she – brings food for communal dining. Soon, she is one of them there, too.

Passionate about food, De Blasi describes the local produce and the markets and the centuries’ old food traditions with eloquence and ease. You read these books with mouth-watering pleasure – and a longing to become an “insider” in Italy, too!

Finally, there’s the food-writing in travel books that have no plots to speak of, but which describe food’s connection to the land, the landscape, the city, the town, the community. These books give you a sense of the rhythm of life there; and you are like a voyeur, looking through the windows of the folks who are living the dream.

Peter Mayle’s A YEAR IN PROVENCE and Frances Mayes’ UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN are two such books. In these, we watch the British Mayle and the American Mayes (with their very similar names!) as they renovate fabulous houses with seemingly unlimited funds. Here, too, we see them prepare the local foods of the season, and discover the bounty of the land.

These are books you can dip into, reading a passage here and there, now and then. And sometimes, you’re rewarded with an unforgettable description of the connection between food and nature and the life cycle, as in this excerpt from UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN:

“The fig flower is inside the fruit. To pull one open is to look into a complex, primitive, infinitely sophisticated life cycle…. Fig pollination takes place through an interaction with a particular kind of wasp about 1/8 of an inch long. The female bores into the developing flower inside the fig. Once in, she delves with her…needle nose, into the female flower’s ovary, depositing her own eggs. If she can’t reach the ovary, she still fertilizes the fig flower with the pollen she collected from her travels. Either way, one half of this symbiotic system is served – the wasp larvae develop if she has left her eggs, or the pollinated fig flower produces seed. If reincarnation is true, let me not come back as a fig wasp. If the female can’t find a suitable nest for her eggs, she usually dies of exhaustion inside the fig. If she can, the wasps hatch inside the fig and all the males are born without wings. Their sole, brief function is sex. They get up and fertilize the females, then help them tunnel out of the fruit. Then they die. Is this appetizing, to know that however luscious figs taste, each one is actually a little graveyard of wingless male wasps? Or maybe the sensuality of the fruit comes from some flavor they dissolve into after short, sweet lives.”

It’s fig season: enjoy them!