Would you believe, WAR AND PEACE ?

The question I was always asked when I said that I was reading WAR AND PEACE was, "Why?" And I think that's a most excellent question: why, indeed?

Well, it's a book one is "supposed" to read; yet I never had. (We students would like to say, "We read in it, but we did not read it…”);

I loved the film, THE LAST STATION, about the sort-of cult that based itself on Tolstoy's writing, and wanted to read one of the books that prompted this;

I wanted to better understand why the Communists never banned the writings of “Count” Tolstoy; and

I read in Hemingway's A MOVABLE FEAST that he'd considered it a great book; and as its style is so different from Hemingway's own, I wanted to see if I could figure out why.

So now, 3973 pages later, I'm going to try to answer these questions!

Let me begin by saying that I don’t think of WAR AND PEACE as a novel at all; and in that, I'm in good company, for Tolstoy himself didn’t think it was a novel and claimed that ANNA KARENINA was his first.

In fact, the romantic stories of Natasha and Andrei and Pierre and Helene seem mere adornments to the book, an excuse to describe battles and to pontificate on philosophy: they are not "real" people, but mere personifications of Tolstoy’s philosophies. And he does not care about them, hastily discarding them once he has laboriously made his point.

From the very beginning of the book, you know that to whomever else Natasha and Pierre may be engaged or married, they will wind up together: and they do.

Pierre is in an unhappy marriage with the beautiful and much-admired, flirtatious Helene, and it is this unhappiness that leads him to wander about, ostensibly to learn the meaning of life.

To that end, he joins various religious groups; tries social experiments on his serfs; engages in war; and “enjoys” heroism and poverty. And just as he finishes his "journey" by deciding that the purpose of life is to live it (!) he finds out that Helene has died. Suddenly. Without reason. In one passing sentence.

This is not a novel...

If anything, it is a political and philosophical tract - and a needlessly long one at that!

On the political side, it stands firmly against war and authority of any kind: neither kings nor generals nor organized religion have his respect. The best that he can say of them is that they are the products of circumstance; and often enough, he treats them with contempt.

To illustrate these points, he spends many hundreds of pages describing in detail the battles fought between the Russians and the armies of Napoleon. The difference between victory and defeat is invariably attributed to the “chance” emotions and determination of the fighting forces: those foot soldiers on both sides who serve mainly as cannon fodder.

People like Napoleon and Emperor Alexander are described as vain and often stupid; and that the “brilliance” attributed to them had been written with hindsight and remains dependent on which historian is doing the describing...

A church of any kind is no better, as it also tries to exert authority over “the people,” while Tolstoy makes clear that the people need to be free, and should listen only to God. (Although God is also an “authority," Tolstoy nevertheless seems to see no contradiction here.)

This, of course, is the philosophical side of the book. Told in more hundreds of pages, Tolstoy espouses his belief that “the people” should live lives free from all those in authority; and that in any case, it is they – and not the Napoleons of the world – who cause the flow of events which we refer to as “history.”

Here – as throughout the book – Tolstoy explains, explains, explains as though he’s giving a geometry lesson: if this happens, then that must happen; if this is the cause, then what came before was the cause of the cause. And he does this over and over again — until he finally decides that we can’t really explain anything that happens because we are unable to go back far enough in our study of causes! Surely, he might have done better than that...!

Now to the questions with which I began:

Of course the Communists liked Count Tolstoy: he was for ‘people-power’ – and the fact that they became the “Rulers” Tolstoy despised was easily ignored by them. Worse still, the cult of “equality” and self-abnegation which centered around Tolstoy ultimately played into the hands of Communist leaders.

As for Hemingway: Tolstoy here displays one of Hemingway’s favorite motifs, that of “grace under pressure.”

Andrei, for example, was a selfish man, ever bored and filled with discontent; then, by experiencing emotional and physical pain and by facing death, he is transformed into a loving, kind and soulful man.

Pierre, too, is transformed by the difficulties he experienced and becomes more self-assured. He is even physically transformed: from a fat, hard-drinking oaf, to a charming and thin man who looks like…well, like Henry Fonda in the film, WAR AND PEACE!

But the writing! Again and again, Tolstoy shows us how people - hundreds of people! - think and act; and then he explains it to us! There is no nuance – and no expectation that we might be able to interpret a person’s emotions, a leader’s behavior, the tragedy of a burned and looted city – on our own. Everything is explained in minute detail, as if to a child.

Compare Tolstoy to Dickens. Dickens shows us the lives of individuals – even if some are drawn as caricatures – and we are allowed to draw our own conclusions about them, and about the reforms necessary to improve life in the England of his day.

Or compare him to Shakespeare....

Tolstoy hated Shakespeare, and had this to say of him:

So: Tolstoy said it for me perfectly....

_________________________________

Well, it's a book one is "supposed" to read; yet I never had. (We students would like to say, "We read in it, but we did not read it…”);

I loved the film, THE LAST STATION, about the sort-of cult that based itself on Tolstoy's writing, and wanted to read one of the books that prompted this;

I wanted to better understand why the Communists never banned the writings of “Count” Tolstoy; and

I read in Hemingway's A MOVABLE FEAST that he'd considered it a great book; and as its style is so different from Hemingway's own, I wanted to see if I could figure out why.

So now, 3973 pages later, I'm going to try to answer these questions!

Let me begin by saying that I don’t think of WAR AND PEACE as a novel at all; and in that, I'm in good company, for Tolstoy himself didn’t think it was a novel and claimed that ANNA KARENINA was his first.

In fact, the romantic stories of Natasha and Andrei and Pierre and Helene seem mere adornments to the book, an excuse to describe battles and to pontificate on philosophy: they are not "real" people, but mere personifications of Tolstoy’s philosophies. And he does not care about them, hastily discarding them once he has laboriously made his point.

From the very beginning of the book, you know that to whomever else Natasha and Pierre may be engaged or married, they will wind up together: and they do.

Pierre is in an unhappy marriage with the beautiful and much-admired, flirtatious Helene, and it is this unhappiness that leads him to wander about, ostensibly to learn the meaning of life.

To that end, he joins various religious groups; tries social experiments on his serfs; engages in war; and “enjoys” heroism and poverty. And just as he finishes his "journey" by deciding that the purpose of life is to live it (!) he finds out that Helene has died. Suddenly. Without reason. In one passing sentence.

This is not a novel...

If anything, it is a political and philosophical tract - and a needlessly long one at that!

On the political side, it stands firmly against war and authority of any kind: neither kings nor generals nor organized religion have his respect. The best that he can say of them is that they are the products of circumstance; and often enough, he treats them with contempt.

To illustrate these points, he spends many hundreds of pages describing in detail the battles fought between the Russians and the armies of Napoleon. The difference between victory and defeat is invariably attributed to the “chance” emotions and determination of the fighting forces: those foot soldiers on both sides who serve mainly as cannon fodder.

People like Napoleon and Emperor Alexander are described as vain and often stupid; and that the “brilliance” attributed to them had been written with hindsight and remains dependent on which historian is doing the describing...

A church of any kind is no better, as it also tries to exert authority over “the people,” while Tolstoy makes clear that the people need to be free, and should listen only to God. (Although God is also an “authority," Tolstoy nevertheless seems to see no contradiction here.)

This, of course, is the philosophical side of the book. Told in more hundreds of pages, Tolstoy espouses his belief that “the people” should live lives free from all those in authority; and that in any case, it is they – and not the Napoleons of the world – who cause the flow of events which we refer to as “history.”

Here – as throughout the book – Tolstoy explains, explains, explains as though he’s giving a geometry lesson: if this happens, then that must happen; if this is the cause, then what came before was the cause of the cause. And he does this over and over again — until he finally decides that we can’t really explain anything that happens because we are unable to go back far enough in our study of causes! Surely, he might have done better than that...!

Now to the questions with which I began:

Of course the Communists liked Count Tolstoy: he was for ‘people-power’ – and the fact that they became the “Rulers” Tolstoy despised was easily ignored by them. Worse still, the cult of “equality” and self-abnegation which centered around Tolstoy ultimately played into the hands of Communist leaders.

As for Hemingway: Tolstoy here displays one of Hemingway’s favorite motifs, that of “grace under pressure.”

Andrei, for example, was a selfish man, ever bored and filled with discontent; then, by experiencing emotional and physical pain and by facing death, he is transformed into a loving, kind and soulful man.

Pierre, too, is transformed by the difficulties he experienced and becomes more self-assured. He is even physically transformed: from a fat, hard-drinking oaf, to a charming and thin man who looks like…well, like Henry Fonda in the film, WAR AND PEACE!

But the writing! Again and again, Tolstoy shows us how people - hundreds of people! - think and act; and then he explains it to us! There is no nuance – and no expectation that we might be able to interpret a person’s emotions, a leader’s behavior, the tragedy of a burned and looted city – on our own. Everything is explained in minute detail, as if to a child.

Compare Tolstoy to Dickens. Dickens shows us the lives of individuals – even if some are drawn as caricatures – and we are allowed to draw our own conclusions about them, and about the reforms necessary to improve life in the England of his day.

Or compare him to Shakespeare....

Tolstoy hated Shakespeare, and had this to say of him:

“I remember the astonishment I felt when I first read Shakespeare. I expected to receive a powerful aesthetic pleasure, but having read, one after the other, works regarded as his best: KING LEAR, ROMEO AND JULIET, HAMLET and MACBETH, not only did I feel no delight, but I felt an irresistible repulsion and tedium…[and am] of firm, indubitable conviction that the unquestionable glory of a great genius which Shakespeare enjoys, and which compels writers of our time to imitate him and readers and spectators to discover in him non-existent merits…is a great evil, as is every untruth.”For me, when I substitute the name “Tolstoy” wherever the name “Shakespeare” was used or implied, I find that it describes exactly how I feel about Tolstoy and his writing…!

So: Tolstoy said it for me perfectly....

_________________________________

Posted by Farshaw@FineOldBooks.com at Monday, August 15, 2011 _________________________________

A 2011 Harlequin Romance

____________________________________

Food Writing

____________________________________

Of course, new books are not quite the same, but you can be a book's “first” owner, the first to hold, read and study it. You can learn from its binding and paper and weight and lettering and smell. You can hold a new book in trust for its future owners. You can become part of its history.

A 2011 Harlequin Romance

I wish I could take credit for writing this, but it was sent to me by my friend George – who claims that he never reads! But he enjoyed reading this and enjoyed sharing it with his friends, and I’m going to do the same.

We don’t know who wrote this, but those of you who read or know of Harlequin Romances will recognize the style immediately; and it’s a perfect rendering -- or, as I like to say, "It's spot on."

So, on this day when so many of us are worrying about Hurricane Irene, I'm sending you some comic relief....

If you’ve read this before, I hope you enjoy it again.

Caution: Like all Harlequin Romances, this is Rated X !

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

A 2011 Harlequin Romance

He grasped me firmly, but gently, just above my elbow, and guided me into a room.

His room.

Then he quietly shut the door and we were alone.

He approached me soundlessly, from behind, and spoke close to my ear in a low, reassuring voice.

“Just relax,” he said.

Without warning, he reached down and I felt his strong, calloused hands start at my ankles, gently probing, and moving upward along my calves, slowly but steadily.

My breath caught in my throat.

I knew I should be afraid, but somehow, I didn’t care. His touch was so experienced, so sure.

When his hands moved onto my thighs, I gave a slight shudder and I partly closed my eyes.

My pulse was pounding.

I felt his knowing fingers caress my abdomen, my ribcage, my firm, full breasts. I inhaled sharply.

Probing, searching, knowing what he wanted, he brought his hands to my shoulders, slid them down my tingling spine and into __________ [fill in the blank].

Although I knew nothing about this man, I felt oddly trusting and expectant.

“This is a man.” I thought. “A man not used to taking ‘No’ for an answer. This is a man who would tell me what he wanted, a man who would look into my eyes and say….

“Okay Ma’am; you can board your flight now.”

THE END

We don’t know who wrote this, but those of you who read or know of Harlequin Romances will recognize the style immediately; and it’s a perfect rendering -- or, as I like to say, "It's spot on."

So, on this day when so many of us are worrying about Hurricane Irene, I'm sending you some comic relief....

If you’ve read this before, I hope you enjoy it again.

Caution: Like all Harlequin Romances, this is Rated X !

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

A 2011 Harlequin Romance

He grasped me firmly, but gently, just above my elbow, and guided me into a room.

His room.

Then he quietly shut the door and we were alone.

He approached me soundlessly, from behind, and spoke close to my ear in a low, reassuring voice.

“Just relax,” he said.

Without warning, he reached down and I felt his strong, calloused hands start at my ankles, gently probing, and moving upward along my calves, slowly but steadily.

My breath caught in my throat.

I knew I should be afraid, but somehow, I didn’t care. His touch was so experienced, so sure.

When his hands moved onto my thighs, I gave a slight shudder and I partly closed my eyes.

My pulse was pounding.

I felt his knowing fingers caress my abdomen, my ribcage, my firm, full breasts. I inhaled sharply.

Probing, searching, knowing what he wanted, he brought his hands to my shoulders, slid them down my tingling spine and into __________ [fill in the blank].

Although I knew nothing about this man, I felt oddly trusting and expectant.

“This is a man.” I thought. “A man not used to taking ‘No’ for an answer. This is a man who would tell me what he wanted, a man who would look into my eyes and say….

“Okay Ma’am; you can board your flight now.”

THE END

_________________________________

Food Writing

I’m not a great cook, but I nevertheless love to read books that include a fair amount of food-writing. By that, I don’t mean cook books – I can’t “taste” food by reading a recipe the way some of my “foodie” friends can. And I also don’t mean books like Gwyneth Paltrow’s, which are essentially recipe books with some background about why the author is interested in food, family and healthy life-choices….

The food books I love are novels, memoirs, travel books, etc., in which food helps drive the plot; or in which food is the vehicle which illuminates the characters, or is shown to “form” their personalities, or describes their relationships with others; or which illustrate how food and cooking can serve to comfort or empower.

This is a large and varied genre.

WOMEN WHO EAT is a collection of essays by women in which they describe their various relationships with food. Some are professional cooks, but most are writers who tell of their feelings and memories of food. It’s a celebration of food and of women who enjoy food without shame or apology.

There are lovely essays about bonding with grandparents while working in the kitchen together; there are reflections about the pleasure of making a meal, because it is one of the few activities in which there are no “loose ends,” as a meal “has a beginning, middle, and end.” Simple and clear.

Because I'd had similar experiences, I especially enjoyed the essay by Pooja Makhijan, whose mother would put exotic “aloo tikis” into her lunch box, so unlike the “American” food her classmates had in theirs – and theirs were the kind of lunches she'd always longed for!

With the same good intentions, my mother would often pack my brown paper bag with a [healthy] whole tomato to bite into like an apple (juice running down my chin and neck) and a sandwich on rich rye bread. And oh, how I, too, longed for a sandwich on real “American” white bread!

Most of the essays in this book were entertaining, though none felt entirely "new." And I hope you'll excuse me if I say that they're a bit like appetizers before the main course....

Most of the essays in this book were entertaining, though none felt entirely "new." And I hope you'll excuse me if I say that they're a bit like appetizers before the main course....

In Ruth Reichl’s memoir, TENDER AT THE BONE, the former restaurant critic and editor of the now defunct GOURMET magazine remembers a childhood that prepared her for a future in the food world. Reichl describes in sometimes hilarious detail, her early and strange connection with food.

Her "manic-depressive" mother loved to entertain, and depending on her mood, or on the latest “bargain” of ready-for-the-garbage food, or whatever decaying carcass she found in her larder, she often served food that was spoiled or moldy. Before the age of 10, Reichl understood that “food could be dangerous” and saw it as her “mission…to keep Mom from killing anybody who came to dinner.” She sometimes stood in front of guests to prevent them from getting to the buffet; and bluntly told her own friends, “Don’t eat that,” as they unsuspectingly plunged their spoons into dishes like bananas in green sour cream.

Her role as “guardian to the guests” made her aware of food in a way that might not have occurred otherwise. She began “sorting people by their tastes” and finding that she could learn a lot about people from the foods they chose and the places in which they liked to eat. And she continued to observe and learn about food as she made her way from New York to a French boarding school in Montreal and a commune in Berkeley; as she came under the wings of people like Alice Waters and James Beard.

Liberally sprinkled with recipes, this adventure in food has a happy ending, as Reichl got to live her passion of cooking and eating and teaching people about food.

Nora Ephron’s HEARTBURN is a slyly fictionalized account of her divorce from journalist Carl Bernstein. The novel’s heroine, Rachel, is a food writer, and Ephron uses food and recipes as the conceit with which to describe Rachel’s relationship and marriage, from its beginning to its end.

Seven months pregnant at the time that she discovers that her husband is having an affair, Rachel reviews the trajectory of their marriage:

When first in love, [she] prepares labor-intensive and time-consuming “crisp potatoes;” when they settle into a married life busy with a child and home improvements, it’s the complacency and self-assuredness of “peanut butter and jelly on white bread.” (Yum!) With the knowledge of her husband’s affair, it’s “heartburn” and a punishing refusal to give him her wonderful vinaigrette recipe. Then it’s self-pity and the comfort of mashed potatoes…. Finally, she accepts that she can do without him, and expresses that acceptance by throwing a pie in his face – and by her willingness to give him that vinaigrette recipe after all: in essence, she is saying, “You can have it, and I’m out of here!”

Forget the Meryl Streep and Jack Nicholson film of the same name; this is a delicious, insightful, and wickedly funny book. And the great recipes are an added bonus.

More and more common in the food-writing genre are the books that tell of people moving to a “foreign” country and navigating their way through that new landscape. And food is a major player in these journeys.

In Marlena De Blasi’s A THOUSAND DAYS IN VENICE, American restauranteur and cookbook writer De Blasi tells of her love-at-first-sight romance with a Venetian man she sees across a crowded room – really! – and of her move to Venice to be with him. And for all its beauty, it’s an inhospitable Venice she comes to, steeped as it is in old traditions which have no room for newcomers.

But De Blasi haunts the local food markets at 5:00 AM each morning, and with her knowledge and love of food, she seduces the locals and becomes “one of them.” Then, she repeats this feat in her sequel, A THOUSAND DAYS IN TUSCANY, where she eats at the small local restaurant to which everyone in the neighborhood – including she – brings food for communal dining. Soon, she is one of them there, too.

Passionate about food, De Blasi describes the local produce and the markets and the centuries’ old food traditions with eloquence and ease. You read these books with mouth-watering pleasure – and a longing to become an “insider” in Italy, too!

Finally, there’s the food-writing in travel books that have no plots to speak of, but which describe food’s connection to the land, the landscape, the city, the town, the community. These books give you a sense of the rhythm of life there; and you are like a voyeur, looking through the windows of the folks who are living the dream.

Peter Mayle’s A YEAR IN PROVENCE and Frances Mayes’ UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN are two such books. In these, we watch the British Mayle and the American Mayes (with their very similar names!) as they renovate fabulous houses with seemingly unlimited funds. Here, too, we see them prepare the local foods of the season, and discover the bounty of the land.

These are books you can dip into, reading a passage here and there, now and then. And sometimes, you’re rewarded with an unforgettable description of the connection between food and nature and the life cycle, as in this excerpt from UNDER THE TUSCAN SUN:

“The fig flower is inside the fruit. To pull one open is to look into a complex, primitive, infinitely sophisticated life cycle…. Fig pollination takes place through an interaction with a particular kind of wasp about 1/8 of an inch long. The female bores into the developing flower inside the fig. Once in, she delves with her…needle nose, into the female flower’s ovary, depositing her own eggs. If she can’t reach the ovary, she still fertilizes the fig flower with the pollen she collected from her travels. Either way, one half of this symbiotic system is served – the wasp larvae develop if she has left her eggs, or the pollinated fig flower produces seed. If reincarnation is true, let me not come back as a fig wasp. If the female can’t find a suitable nest for her eggs, she usually dies of exhaustion inside the fig. If she can, the wasps hatch inside the fig and all the males are born without wings. Their sole, brief function is sex. They get up and fertilize the females, then help them tunnel out of the fruit. Then they die. Is this appetizing, to know that however luscious figs taste, each one is actually a little graveyard of wingless male wasps? Or maybe the sensuality of the fruit comes from some flavor they dissolve into after short, sweet lives.”

It’s fig season: enjoy them!

_________________________________

Some Thoughts About Books as Objects

In this day of eBooks and iBooks and digital publishing; in this day when electronic displays are so sophisticated that one can actually turn pages on the screen and highlight passages and leave yellow sticky notes on the electronic page; in this day when one can carry an entire library of books in a convenient electronic case weighing no more than a pound or two; one is left to wonder about the future of books as physical, printed objects.

I sell books. Not eBooks, but real books with pages made of paper. Books rare and old. My books smell of paper and ink. The pages are browned by age, and sometimes smudged with use.

Some are inscribed to a friend, with an explanation of why the book was chosen and given; some are inscribed by the author to an admirer, or colleague. Some are signed by an owner in childish lettering or in adult script. Some have the signatures of notable figures. (These “association” copies are among my favorites.) Each of these adds to the pleasure of the book, to the understanding of it. And you are linked to the people who’d owned it before you.

Some are “extra illustrated,” with original sketches or paintings by an artist; or with pertinent extras bound into the book.

I once had an “extra illustrated” copy of Morley’s LIFE OF GLADSTONE which was a 3 volume set that had been stretched into 10 volumes as a result of the inclusion of so many pertinent extras: engraved portraits of Gladstone and members of his political English circle, hand-written letters from John Stuart Mill, Benjamin Disraeli and many others. In the hands of its owner, this modest book had become a treasure-trove of information, a document and history of the period.

Some of my books have traveled to me from across continents and generations. How did a lovely illustrated book on palmistry (with beautiful endpapers made from old velum scrolls) make its way from 16th century Italy to 21st century Massachusetts? How many people touched it, carried it, cared for it? How did they protect it as it crossed oceans and time?

For me, there is a kind of magic to this; there’s tremendous intimacy shared with those who came before you; and there are innumerable tactile pleasures as well – all of which imbue the words with meanings that cannot be conveyed in words alone.

You must hold a real book in your hand, smell the pages, examine the type face, the spacing between letters; must note the shape and size of the book, the weight of it. Only then can you experience the book’s full import. And its magic.

A book as an object is a piece of history.

If you care to learn it, you can know a book’s age and place of publication just by recognizing the font used; or by how much spacing (leading) there is between lines of text; or by the amount of linen or acid in the paper; or whether the page edges were individually “cut” for reading as one went along, or machine cut as is common for newer books; or by the garish and graphic covers of pulp paperbacks from the ‘40’s and ‘50’s; or by seeing whether the engravings are copper or steel; or by noting the use of the letter “f” for the letter “s” and the like. You can gage the tastes of the period through the bindings most common to it.

You can spot a smuggled copy of the banned James Joyce book, ULYSSES, even though it has no title on it – or has a fake title, all the better for smuggling! – because the book’s shape is that of an almost perfect square.

I have friends who have a set of Homer that belonged to Elizabeth Barrett Browning. Imagine!

Rusty Mott, a bookseller in Sheffield Massachusetts, once had Melville’s copy of William Davenant’s WORKS, London: 1673. He catalogued it [in part] as follows:

“Signed by Melville on the flyleaf: ‘Herman Melville / London, December, 1849 / New Year’s Day, at sea).’

With pencil notations by Melville…comprising check marks, x’s, sidelines, question marks, underlining, plus comments…all illustrating passages Melville felt important, such as whales, religion, monarchs and subjects, nature, knowledge, punishment of sin, etc. In one place he has written ‘Cogent;’ in another, ‘This is admirable,’ and in a third, he compliments Davenant....

The existence of this example of Melville’s reading has been known for some time but has been ‘lost’ since 1952.”

Imagine!

What a remarkable book! There’s so much to learn about both authors as a result of Melville’s notations. How wonderful it was to have held that book in my hands: Melville’s own book! And now, some other lucky person can hold and study it. And care for it.

I once had the prayer book belonging to Carlota, wife of Emperor Maximilian of Mexico. Placed on the throne by Napoleon III, Maximilian was eventually captured and executed by Mexican Republican forces. At the time, Carlota was in Europe trying to get support for her husband. After learning of his death, she had an emotional collapse and lived in seclusion for the rest of her life.

What were those light round spots and ripples on some of the pages of her prayer book? Were they tears? And which passages of the book brought about those tears? Of course, I’ll never know the answers to any of those questions, but I’m free to imagine and relate to the scene in a way that is not possible without having the book – the object and not just the words – in my hands. As I held the book, Carlota and I were linked across space and time. This is magic.

Shakespeare folios also feel quite magical. All but a few of them are in libraries, but many years ago, we managed to buy a 2nd and 4th folio for a client; and we had them at home for a while. Bound in well-cared-for contemporary (of the period) leather, they sat on a table in our living room. Whenever our 4 children were near the table, they became hushed, almost tip-toeing as they walked by: they were so beautiful, so old, so...expensive!

Adam, the youngest, was only 4 at the time. He and his older siblings would sometimes stand and look at the folios from a respectful distance. Adam would put his hands behind his back and lean forward so far that he was in danger of falling.

One day he asked, “Can we touch them?” This broke the “spell,” and the big girls were quick to say, “Of course we can; they’re books; they’re meant to be touched and read! They’ve been touched and read for centuries!” And then they touched them. Carefully. Very carefully.

First they caressed the bindings, stroking the leather. Then the two “big” girls – Sarah,12 and Johanna,14 – opened the books and slowly turned the pages, allowing Abigail and Adam, the two little ones, to see and carefully touch the pages. The paper was rippled, and the pages crackled when turned.

Except for that crackle, there was silence, almost a holy silence…. They treated the books with reverence and awe. Even at their young ages, they knew that they were in the presence of something important and wondrous. They felt the magic, and remember it still....

Except for that crackle, there was silence, almost a holy silence…. They treated the books with reverence and awe. Even at their young ages, they knew that they were in the presence of something important and wondrous. They felt the magic, and remember it still....

Of course, new books are not quite the same, but you can be a book's “first” owner, the first to hold, read and study it. You can learn from its binding and paper and weight and lettering and smell. You can hold a new book in trust for its future owners. You can become part of its history.

Give your eReader a rest, grab a real, printed book: and feel the magic.

__________________________________

______________________________

Telling Stories Without Using Words

Books, too, can tell stories without words.

All of the other films released in time for the awards season are ones with words, often lots of them! But the words do not necessarily move the plot along, or foreshadow what’s to come, or reveal a person’s character.

I hope you enjoy this “story” that's been all over Facebook; the words are very important.

_________________________________

Posted by Farshaw@FineOldBooks.com at Saturday, February 4, 2012 ____________________________________

"Reports of My Death Are Greatly Exaggerated."

_________________________________

Posted by Farshaw@FineOldBooks.com at Friday, August 31, 2012 ____________________________________

The Willing Suspension of Disbelief:But can you possibly believe this?

_______________________________________________

Telling Stories Without Using Words

Is it possible to tell a story without using words?

Yes.

It’s been done for centuries; and sometimes — even today — it can be the most effective way to tell a particular story well.

Last month the Hollywood Foreign Press Association gave the prestigious Golden Globe award for best film in the comedy/musical category to THE ARTIST, a film without words: a silent movie. Never mind that this film was not exactly a comedy; this silent film was appreciated by both the critics and the movie-going public; they were moved, touched, and involved in a story presented silently on the screen.

Words and the stories they tell seem inseparable, but neither is necessary for the other.

Cave paintings, of course, are an early example of story telling without words.

Those who have been in or have seen photos of the caves in Lascaux remain astonished by the sophistication of the art and “stories” painted on its walls.

Words and the stories they tell seem inseparable, but neither is necessary for the other.

Cave paintings, of course, are an early example of story telling without words.

Those who have been in or have seen photos of the caves in Lascaux remain astonished by the sophistication of the art and “stories” painted on its walls.

|

| Cave Painting, Lascaux |

|

| Cave Painting, Lascaux |

Paintings, sculptures, and music continue to tell us stories: of devotion, of history, of emotion, of thought.

Pantomimes have been performed for centuries. Even in the most sophisticated of societies, people like the famous beauty, Lady Hamilton, gave performances of what she called “attitudes:” frozen poses and tableaus from myths and other tales.

Pantomimes have been performed for centuries. Even in the most sophisticated of societies, people like the famous beauty, Lady Hamilton, gave performances of what she called “attitudes:” frozen poses and tableaus from myths and other tales.

|

| Lady Hamilton as a Bacchante, by Marie Louise Élisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, 1790–1791 |

Books, too, can tell stories without words.

I’m not thinking about comic books with their “bubbles” of dialogue; I’m not even talking about more serious “graphic novels” like Art Speigelman’s Pulitzer Prize winning MAUS: A SURVIVOR’STALE, which uses cartoon art to tell the story of his father’s survival in Nazi Germany; for in these, too, there is dialogue, and there are words to describe the characters’ actions or thoughts.

What comes to my mind is the Belgian artist Frans Masereel’s stunning woodcut novels: graphic, powerful stories and social criticism told without a single word.

Through the stories he tells in woodcuts,

Through the stories he tells in woodcuts,

“Masereel pitilessly castigated man’s ugliness, while praising his beauty. With rare force, he carved the image of the misery man calls down upon himself, but which he has the power to prevent if he would. With the intensity that characterizes him, he extols humanity, and a society…in which all men are brothers.”

— (Maurice Naessents, Preface to AVERMAETE)

|

| Woodcut from Masereel's THE CITY |

So powerful were Masereel’s novels — despite having no words — that the Nazi’s banned his books; and he was even forced to flee from Paris during World War II.

|

| THE CITY |

Masereel’s work had a lasting influence on many artists — most famously Lynd Ward and contemporary artist Eric Drooker — and his work remains highly esteemed throughout the world.

|

| Lynd Ward from GODS' [sic] MAN |

|

| Lynd Ward |

Film would seem a natural medium for telling stories without words; it was, after all, first called “motion” pictures! But though that’s how film began, it's "talking" — speaking words — that's become the way to tell a story on film. Even so, today's movies have elements of the silent film within them. Chase scenes, for example, have become a staple of many films, and would be just as effective with silent movie style musical accompaniment as with the screeching tires which accompany them now.

THE ARTIST has stripped away the words and is a throwback to that earlier way of story-telling on film.

Anyone who’s ever seen a movie knows the basic story of THE ARTIST: it's the story of Greta Garbo, moving gracefully from silent movies to “talkies” as opposed to her leading man, John Gilbert, who could not manage it; or it’s SINGING IN THE RAIN — the famous Gene Kelly film which tells the story of that change. It’s also A STAR IS BORN (1937, 1954,1976) and countless other stories about show business success and failure.

Yet THE ARTIST manages to make this old story new — and ironically, it makes it new by using an old format: it’s black and white and silent.

And this film is much more than simply a retelling of those familiar stories. As actor James Cromwell (who plays the chauffeur in the film) says in his article, ”Why the Quietest Movie in My Career is Making the Most Noise,” the film is

THE ARTIST has stripped away the words and is a throwback to that earlier way of story-telling on film.

Anyone who’s ever seen a movie knows the basic story of THE ARTIST: it's the story of Greta Garbo, moving gracefully from silent movies to “talkies” as opposed to her leading man, John Gilbert, who could not manage it; or it’s SINGING IN THE RAIN — the famous Gene Kelly film which tells the story of that change. It’s also A STAR IS BORN (1937, 1954,1976) and countless other stories about show business success and failure.

Yet THE ARTIST manages to make this old story new — and ironically, it makes it new by using an old format: it’s black and white and silent.

And this film is much more than simply a retelling of those familiar stories. As actor James Cromwell (who plays the chauffeur in the film) says in his article, ”Why the Quietest Movie in My Career is Making the Most Noise,” the film is

“not just an homage to a bygone era, it [is] a story that would be as contemporary today as it was [then]…[as it depicts] the idea of the world moving on without you, and the knowledge…that we are replaceable.”

Who among us cannot identify with that? (Certainly, booksellers can!) And what better way to make that universal fact seem timeless than to illustrate it using the storytelling methods of a “bygone” era?

All of the other films released in time for the awards season are ones with words, often lots of them! But the words do not necessarily move the plot along, or foreshadow what’s to come, or reveal a person’s character.

A DANGEROUS METHOD purports to show the birth of modern psychoanalysis through the interactions between Freud, Jung and their patient (the future — and first female — psychoanalyst), Sabina Speilrein. This is a wordy movie in which the words serve to obscure what is actually occurring: Jung is using word-therapy to rationalize an affair with this young woman; and to establish himself and his methods as superior to Freud’s.

Words, words, words: yet everything important we learn about Jung in this film is learned from his actions: the way he enjoys beating his female protégé; the way he “talks” his reluctant mentor, Freud, into joining him on a working tour of America, yet thinks nothing of taking his privileged, clueless self to a first-class berth and leaving Freud — speechless! — in tourist. And finally, we get to know Jung’s driven personality best through the words written on the screen at the film’s end: he had a nervous breakdown and emerged from that breakdown as one of the most influential of psychiatrists.

In a better film, these written words would not have been necessary; perhaps the film needed more action. Certainly, the spoken words didn't avoid the need for writing that explanatory note on the screen….

Words, words, words: yet everything important we learn about Jung in this film is learned from his actions: the way he enjoys beating his female protégé; the way he “talks” his reluctant mentor, Freud, into joining him on a working tour of America, yet thinks nothing of taking his privileged, clueless self to a first-class berth and leaving Freud — speechless! — in tourist. And finally, we get to know Jung’s driven personality best through the words written on the screen at the film’s end: he had a nervous breakdown and emerged from that breakdown as one of the most influential of psychiatrists.

In a better film, these written words would not have been necessary; perhaps the film needed more action. Certainly, the spoken words didn't avoid the need for writing that explanatory note on the screen….

TINKER TAILOR SOLDIER SPY is a wordy film about British spies that is based on the John Le Carre novel of the same name. This is no James Bond thriller: there is little action; there are no car chases; and few murders. Instead, it’s mainly about words and paper. As must be true of real espionage, the words are often meant to obscure, are meant to cover up what’s actually occurring. (This slow-paced, wordy film can be so obscure that some reviewers joked that it should be seen early in the day, when the mind is still “fresh…!”)

It’s an interesting film; yet, perhaps the most exciting scene — the one that has you sitting on the edge of your seat, the one which makes you understand that these wordy old men do dangerous work and can themselves be dangerous — is a scene with almost no words.

Throughout the film, one is silently shown stacks of papers that are housed in intelligence headquarters: papers read, filed, put on dumbwaiters, stored. In this suspenseful scene, we watch a spy try to steal one of them. There he is in a building filled with other spies, trying to remove classified papers from the building. Without getting caught.

He needs to sign in and out; he needs to relinquish his briefcase; he needs to make appropriate small-talk; he needs to keep his cool…. This scene is riveting, and gives one a fuller picture of the world of spies and spying: a fuller story than the one they’d been conveying with words.

It’s an interesting film; yet, perhaps the most exciting scene — the one that has you sitting on the edge of your seat, the one which makes you understand that these wordy old men do dangerous work and can themselves be dangerous — is a scene with almost no words.

Throughout the film, one is silently shown stacks of papers that are housed in intelligence headquarters: papers read, filed, put on dumbwaiters, stored. In this suspenseful scene, we watch a spy try to steal one of them. There he is in a building filled with other spies, trying to remove classified papers from the building. Without getting caught.

He needs to sign in and out; he needs to relinquish his briefcase; he needs to make appropriate small-talk; he needs to keep his cool…. This scene is riveting, and gives one a fuller picture of the world of spies and spying: a fuller story than the one they’d been conveying with words.

CARNAGE is a Roman Polanski film based on the play, GOD OF CARNAGE. Like the play, this is a wordy story of two couples — strangers — meeting to discuss what’s to be done about a violent playground altercation between their 9-year old sons.

Theater is a wordy medium. Even when film was silent, theater was not. Nevertheless, in this wordy play which has four adults say unbelievably horrible things to one another, the scene in the play which most roused the audience was a strictly visual one: a guest vomits all over a table laden with precious “cocktail table” books. The audience roars.

The film is almost like a stage reading, but even the shortening of the title shows an attempt here to be less wordy and more visual. As with the play, that very visual vomit scene gets the most audience attention. But the thing that brings the point of the story home — and is not in the play — is a wordless scene at the end of the film.

For almost two hours, we listen to four adults saying the most outrageous and uncivilized things; we see all kinds of fighting — couple against couple, husbands against wives, women against men, men against women — in their attempt to deal with their children’s bad behavior. We watch as relationships change, perhaps permanently. Then, in this final scene, while their parents are still arguing, we're shown [from a silent and respectful distance] the two boys playing together again: as though nothing bad had ever happened between them. The boys are more civilized, more rational -- more adult! -- than their parents.

Here, we see silence telling a story, and telling it very well. Again, James Cromwell makes the point quite clearly:

Theater is a wordy medium. Even when film was silent, theater was not. Nevertheless, in this wordy play which has four adults say unbelievably horrible things to one another, the scene in the play which most roused the audience was a strictly visual one: a guest vomits all over a table laden with precious “cocktail table” books. The audience roars.

The film is almost like a stage reading, but even the shortening of the title shows an attempt here to be less wordy and more visual. As with the play, that very visual vomit scene gets the most audience attention. But the thing that brings the point of the story home — and is not in the play — is a wordless scene at the end of the film.

For almost two hours, we listen to four adults saying the most outrageous and uncivilized things; we see all kinds of fighting — couple against couple, husbands against wives, women against men, men against women — in their attempt to deal with their children’s bad behavior. We watch as relationships change, perhaps permanently. Then, in this final scene, while their parents are still arguing, we're shown [from a silent and respectful distance] the two boys playing together again: as though nothing bad had ever happened between them. The boys are more civilized, more rational -- more adult! -- than their parents.

Here, we see silence telling a story, and telling it very well. Again, James Cromwell makes the point quite clearly:

“Ultimately, acting on any film…is telling the truth while pretending it’s fiction. It’s often very difficult to do with words...because [words] so rarely mean what we use them to say.”I can end here — but I won’t; because although "a picture is worth a thousand words," often enough, it’s not: you need words to know the whole story.

I hope you enjoy this “story” that's been all over Facebook; the words are very important.

Posted by Farshaw@FineOldBooks.com at Saturday, February 4, 2012 ____________________________________

"Reports of My Death Are Greatly Exaggerated."

No: not Mark Twain this time, but the Printed Book.

Several times now, I’ve written about how the media keeps reporting the death of the printed book; about how printed books are used as a medium for sculpture;

about how many use them purely as “decorative” items; about how the printed book is not as “pure”an experience as reading an eBook. We book lovers – and booksellers! – can be moved to feelings of despair.

But despair not.

Negative reports about booksellers and books are a part of the printed book’s history from its birth. Gutenberg’s introduction of movable type allowed large printing runs rather than the calligraphed scrolls that required the laborious and skilled labor of scribes; but with the publication of the GUTENBERG BIBLE, the question of whether books should be made for ‘all’ to read was cause for worry – and even anger – as the church wanted to be the only interpreter of the holy book.

|

| Gutenberg Bible at the Ransom Center, University of Texas |

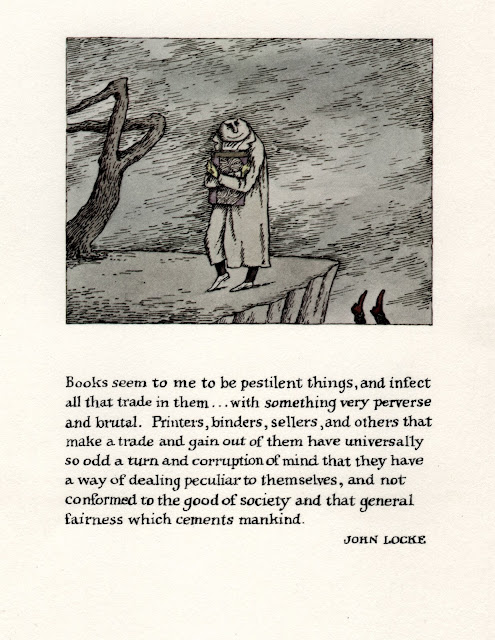

In a more recent diatribe, no less a philosopher than John Locke wrote this of books and booksellers in 1704:

|

| by Edward Gorey for his agent, John Locke, the lineal descendant of philosopher Locke |

So today’s preponderance of wishes for and reports on the “death of the printed book” is, perhaps, merely the most recent in a long history of conversations on this topic.

And along with examples of [what I consider] the misuse and denigration of the printed book, I’ve had enthusiastic response to posts about the uniqueness of books as objects; of how people love rooms filled with books, love public and personal libraries of all kinds; how a room full of books can be descriptive of its owner’s character. (Perhaps that’s why rooms meant to convey intelligence – as in the before mentioned political interview show – often have as background a wall of overstuffed bookshelves.

People post videos and pictures of libraries on Facebook and elsewhere.

|

| Library in Paris |

|

| Exeter Library |

|

| One of my favorites. |

They create imaginative bookshelves and "Little Libraries."

| |||

| Little Free Library |

|

| Little Free Memorial Library |

They go to book readings and have books signed by their authors.

Last week I went to a well-attended book reading of author Matthew Dicks’ new novel, MEMOIRS OF AN IMAGINARY FRIEND. It’s a book about…well, it’s a book about a boy and his imaginary friend! But it’s also a love story; a story of friendship, devotion and self-sacrifice; a story that celebrates and cherishes those who are “different” from most, and helps the reader to understand and cherish them too.

This is the author’s third book, and with each book, the audience for his readings grows. Why?

Matt is a good and entertaining reader; is that why they drive long distances to see him? Readers enjoyed his first two novels; is that why they came?

Of course, the answer is “yes” to both those questions. But I believe that they also came to make a connection with the author and with other like-minded readers; they want to make a connection through a book.

And I mean a printed book.

After all, had they come just to hear him, they could have downloaded the book and had the eBook in a minute: no need to stand in line to pay for it.

But it was the printed book – a “real” book! – that made “real” communication between author and reader and other readers possible.

“To whom should I inscribe this,” asked the author?

And there’s the opening: who? why? Discussions about this novel and his previous ones began; Matt even recommended books by other authors that he admired.

And there on the half-title is the reader’s “collaboration” with the author on the words the author has inscribed there. Real. Tangible.

What’s his penmanship like? Did he use marker or ballpoint? (Try to get ballpoint; have one with you just in case!) You can feel the paper – a bit rough in this book – and the indentations made by the pen: deep? shallow? You can remember how you felt and how the author looked during this collaboration. And you can bring the book home with you and revisit this page again and again. It is not just words; it’s personal: it’s your book and nobody else’s!

Read it; hold it, touch it, smell it. Use your senses to enjoy the complete experience of reading.

Take the sense of smell, for example. All books have a scent, as do the rooms that house them. MEMOIRS OF AN IMAGINARY FRIEND smells a bit woody, which works well with the slight roughness of the paper and, coincidentally, can be imagined to reflect the plot and mood of the book. Lost (as if in a forest) and then found! A stretch, I know, but such a stretch is possible for the reader to imagine with a printed book and is simply not possible with an eBook, not possible with words alone.

Old books have a particular scent of their own which, of course, has nothing to do with the book’s subject; the paper in books have a particular property that makes books smell so good, especially as they age:

The printed book is not dead; and for me it remains a truism that, as Bell's Books' logo has it,

_________________________________

Posted by Farshaw@FineOldBooks.com at Friday, August 31, 2012 ____________________________________

The Willing Suspension of Disbelief:But can you possibly believe this?

It's a given that when we watch theater or film,

we must bring with us "the willing suspension of disbelief;" that is, we

agree to believe that what we're seeing and hearing is "true."

It

doesn't matter that the stage is often empty or that the sets are only a

suggestive representation of a real place; it doesn't matter that those

"cats" singing and writhing in front of us are actually dancers; or

that a young man bitten by a radioactive spider develops web-making

powers and the ability to "leap tall buildings in a single bound" and so

becomes that altruistic defender of "good" known as Spiderman (with

apologies to Superman).

But

once viewers suspend their disbelief and accept the work's premise,

behavior that is illogical for the world we agreed to accept is rarely

tolerated by viewers and can lead to eye-rolling and even laughter.

Imagine if that "cat" on the stage were suddenly and without reason to

begin flying and chirping like a bird!

There are, of course, less abrupt ways in which the viewer's trust can be broken.

Because

it begins with one absurdity after another, the new film, SEEKING A

FRIEND FOR THE END OF THE WORLD, prepares the audience for a comedy.

First,

we watch people listen to an upbeat radio announcer say that "The final

mission to save mankind has failed," and that an asteroid will hit and

destroy the world in three weeks; the announcer continues (in a radio

voice that we can all recognize) by saying that, "We'll be bringing you

the countdown to the end of days along with all your classic rock

favorites." This is funny!

Also

funny are employers extending 'casual Fridays' to the entire week;

people arranging blind dates; policemen giving speeding tickets;

homeowners mowing lawns and having garage sales; and looters stealing

TV's and such -- all in the context of three weeks left to live!

This is funny stuff! Viewers agree to believe this premise and as expected, they laugh.

Then

suddenly, the movie shifts -- almost completely! -- into sadness,

tragedy, and the desperate need of people to connect and to find a

meaning for their lives. There are suicides; there is romance and new

love; there are heartbreaking efforts to find closure for past hurts;

there is longing to reunite with family and to reconcile with God....

Viewers

are not prepared for this; they become silent; some even leave the

theater: we are no longer willing partners to the drama of this film.

Another common way in which the audience’s

trust can be broken is through a preponderance of unbelievable

coincidences, some of which appear "just in time." This can definitely

bring on the eye rolls, as we think, "Do you really expect me to believe

that?"

But perhaps we’re

too harsh in thinking so, as there's that other commonly held belief

that "truth is stranger than fiction." And often enough, it is: it just

happened to me.

I went to my son Adam's graduation ceremonies at Stanford on June 16th.

|

| Proud |

After the ceremonies and

celebrations, I fell and broke my wrist. Badly. I was rushed to the ER

where, of course, we spent many, many hours -- some of them with me in “traction” in a Chinese Finger Trap like the ones I played with as a child!

|

| Low tech for a change! |

Of

course, I felt awful about spoiling his occasion, but Adam was nice

enough to say that he'd been worried about how to entertain us for the

rest of the day and that I'd solved that problem for him!

|

| Me in my Stanford souvenir hospital gown. |

Would you believe that my timing would be so good that my injury did not interfere with Adam’s graduation ceremonies?

My

healing did not go well, and when I got back to Arizona, my friend Jo

insisted on taking me to the ER. I've had reason to go to the ER before

(not for me) and always went to the Mayo Clinic -- might I have a thing

for "brand" names? -- so I assumed that we'd be going there; but my

friend preferred a new hospital in north Scottsdale, and as she was the

driver, I agreed.

My

splint was too tight and had to be redone. Steve, my PA, asked where I

was from and did a double-take when I said the Berkshires. "What's

wrong?" Jo asked, whereupon he told us that he'd accepted a position at

the Berkshire Medical Center and would be starting there at the end of

July!

Would

you believe that I would go to a hospital that I'd never have thought

to go to, and there meet someone who will be a Berkshire neighbor?

Would you believe that Steve would happen to be on duty on that particular day; and that with the very many people working in the ER, he would be my doctor?

Steve said that he was looking for somewhere to live while he went house-hunting, and Jo said, “Helen

knows everybody in the Berkshires including all of the realtors." (This

is not quite true, but close enough.) She also told him that I had a

space adjacent to the bookstore that I was thinking of renting as a

sort-of seasonal B&B -- make that a seasonal “B”:

get your own muffins! -- and that it would be the perfect place for

him. Steve agreed that it seemed a good solution. Soon, people kept

coming into my room -- the doctor, the receptionist, the admitting

nurse, the splint-maker, and so on -- just to tell me how wonderful

Steve is and how much I'd like having him as a tenant.

Would

you believe that I first told Jo my thoughts about renting the space

during our drive to the hospital? Would you believe that I would have

Jo -- my ultimate booster! -- with me when Steve came into the room?

Would you believe that I had a potential renter almost as soon as I had

the thought of renting? And would you believe that I, still a bit

uncertain about renting space furnished with so many beautiful things

that I love, would "bump into" a potential renter who came with such a

bevy of enthusiastic recommendations?

|

| Store |

I

had wrist surgery yesterday and I won't be able to return to the

Berkshires until the middle of the month; so, I'm hoping for one more

happy coincidence: that my customers and friends just happened

to be 'away' or 'busy' during the beginning of July, and that they'll

be ready and waiting to come to my bookstore upon my return.

And why can't that be true? After all, "truth is stranger than fiction...!"

_______________________________________________

Posted by Farshaw@FineOldBooks.com on July 5, 2012_______________________________________________

_______________________________________________